Python Course Nontapat Thaiprayoon

01 Basics

- Hello World

- Variables and Types

- Basic Operators

- String Formatting

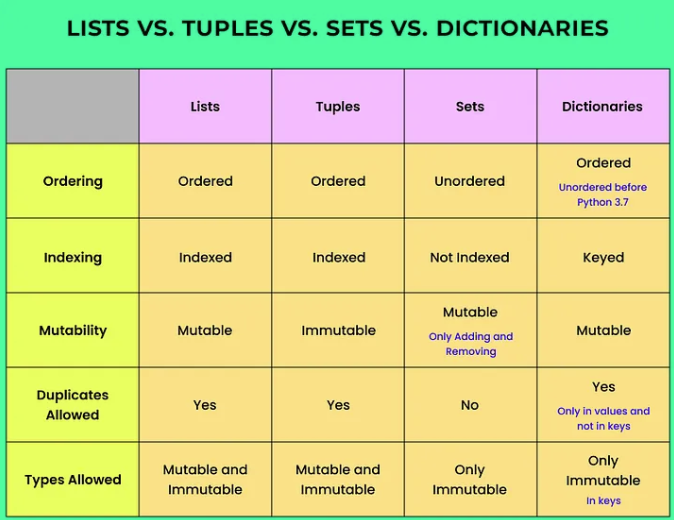

- Lists and Tuples

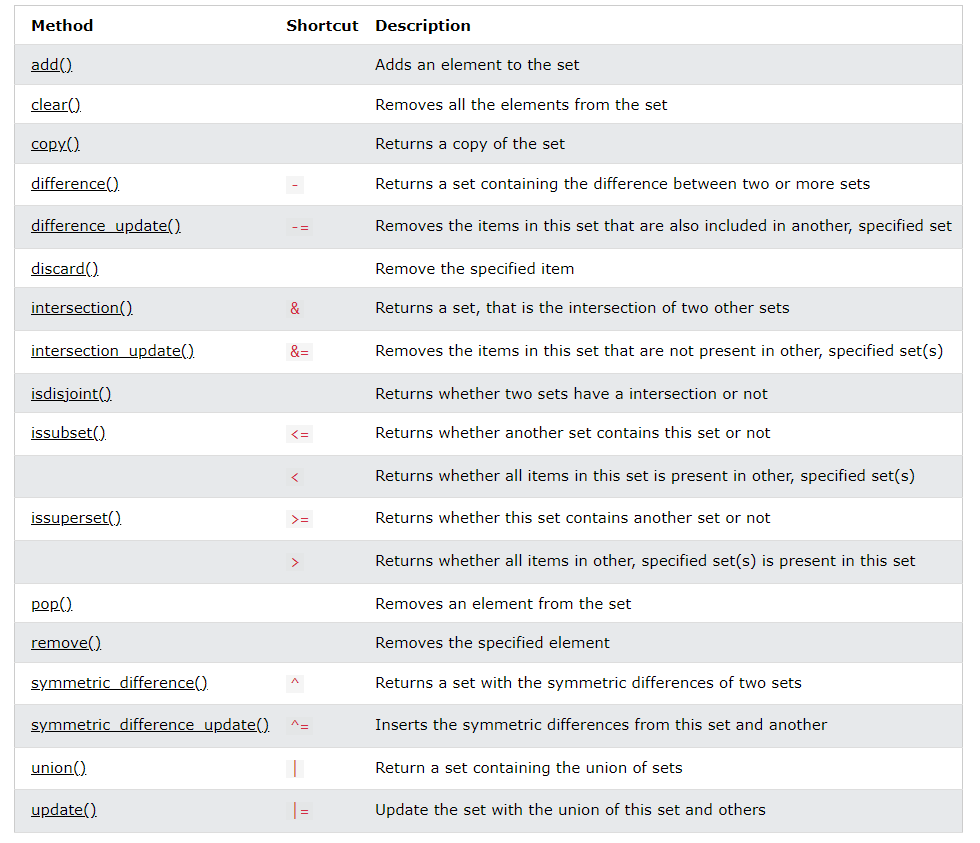

- Sets

- Conditions

- Loops

- Functions

- Dictionaries

>Hello World

Python is a very simple language, and has a very straightforward syntax. The simplest directive in Python is the “print” directive - it simply prints out a line.

Python

print("Hello, World!")

Java

public class HelloWorld {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("Hello, World!");

}

}

C

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

printf("Hello, World!\n");

return 0;

}

C++

#include <iostream>

int main() {

std::cout << "Hello, World!" << std::endl;

return 0;

}

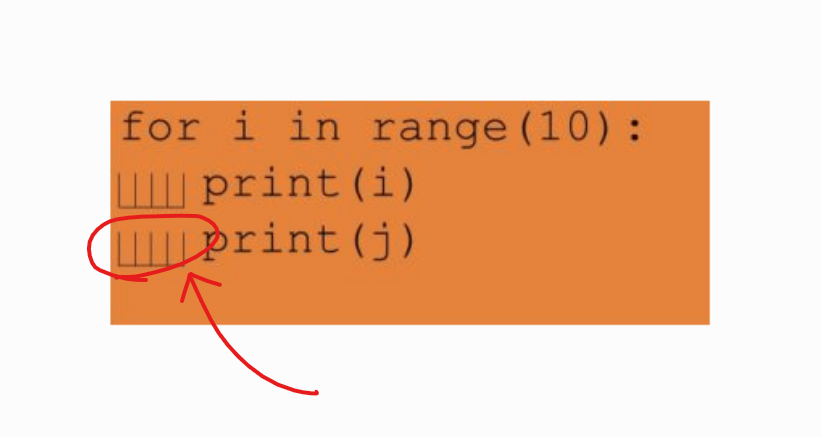

Indentation

Python uses indentation for blocks, instead of curly braces. Both tabs and spaces are supported, but the standard indentation requires standard Python code to use four spaces.

x = 1

if x == 1:

# indented four spaces

print("x is 1.")

>Variables and Types

Python is completely object oriented, and not “statically typed”. You do not need to declare variables before using them, or declare their type. Every variable in Python is an object.

Numbers

Python supports two types of numbers:

- integers(whole numbers)

- floating point numbers(decimals).

myint = 7

print(myint)

print(type(myint))

and

myfloat = 7.0

print(myfloat)

print(type(myfloat))

myfloat = float(7)

print(myfloat)

print(type(myfloat))

Strings

Strings are defined either with a single quote or a double quotes.

myint = 7

print(myint)

print(type(myint))

There are additional variations on defining strings that make it easier to include things such as carriage returns, backslashes and Unicode characters.

one = 1

two = 2

three = one + two

print(three)

hello = "hello"

world = "world"

helloworld = hello + " " + world

print(helloworld)

Assignments can be done on more than one variable “simultaneously” on the same line

a, b = 3, 4

print(a, b)

Mixing operators

one = 1

two = 2

hello = "hello"

print(one + two + hello)

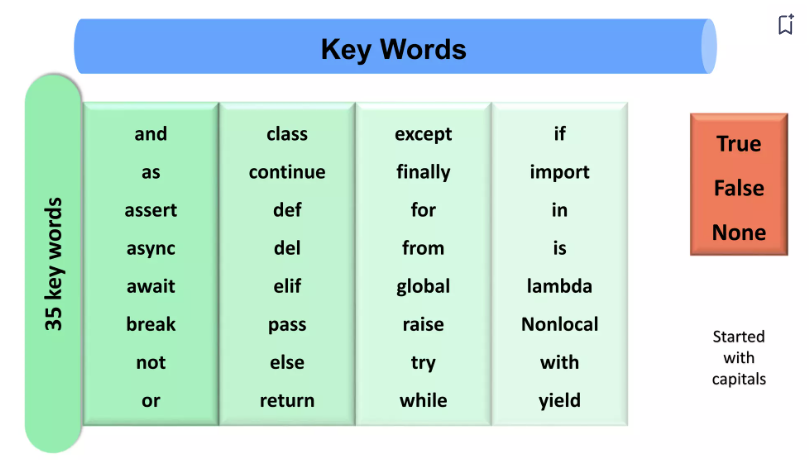

Reserved Words

A python keyword is a reserved word which you can’t use as a name of your variable, class, function etc. These keywords have a special meaning and they are used for special purposes in Python programming language.

>Basic Operators

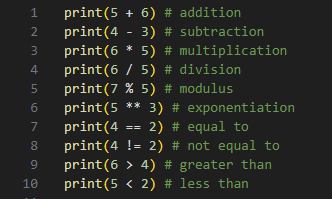

Arithmetic Operators

The addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division operators can be used with numbers.

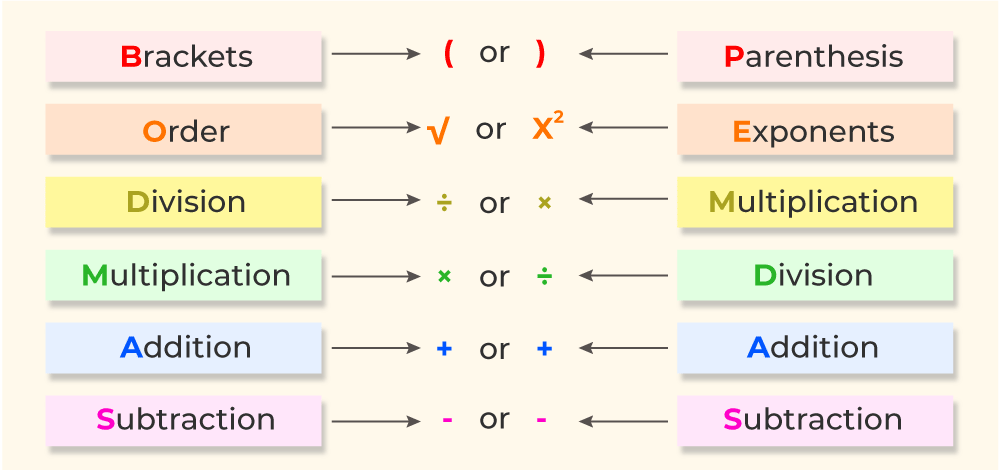

number = 1 + 2 * 3 / 4.0

print(number)

Another operator available is the modulo (%) operator, which returns the integer remainder of the division. dividend % divisor = remainder.

remainder = 11 % 3

print(remainder)

Using two multiplication symbols makes a power relationship.

squared = 7 ** 2

cubed = 2 ** 3

print(squared)

print(cubed)

Using Operators with Strings

Concatenating strings using the addition operator

helloworld = "hello" + " " + "world"

print(helloworld)

Using Operators with Lists

Lists can be joined with the addition operators

even_numbers = [2,4,6,8]

odd_numbers = [1,3,5,7]

all_numbers = odd_numbers + even_numbers

print(all_numbers)

Just as in strings, Python supports forming new lists with a repeating sequence using the multiplication operator

print([1,2,3] * 3)

>String Formatting

Python uses C-style string formatting to create new, formatted strings. The ”%” operator is used to format a set of variables enclosed in a “tuple” (a fixed size list), together with a format string, which contains normal text together with “argument specifiers”, special symbols like “%s” and “%d”.

name = "John"

print("Hello, %s!" % name)

To use two or more argument specifiers, use a tuple (parentheses):

name = "John"

age = 23

print("%s is %d years old." % (name, age))

Any object which is not a string can be formatted using the %s operator as well. The string which returns from the “repr” method of that object is formatted as the string.

mylist = [1,2,3]

print("A list: %s" % mylist)

Here are some basic argument specifiers you should know:

- %s - String (or any object with a string representation, like numbers)

test = "a book" print("This is %s !" % test) - %d - Integers

test = 19 print("I am %d years old" % test) - %f - Floating point numbers

test = 190.985 print("I am %d years old" % test) - %.<number of digits>f - Floating point numbers with a fixed amount of digits to the right of the dot.

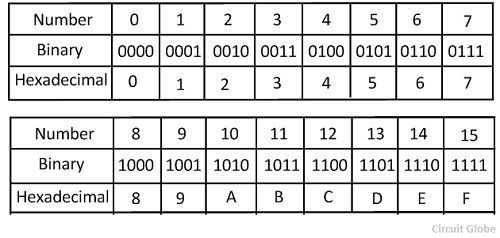

test = 190.985 print("I am %.2f years old" % test) - %x, %X - Integers in hex representation (lowercase/uppercase)

test = 15 print("I am %x years old" % test)

Exercise

You will need to write a format string which prints out the data using the following syntax: Hello John Doe. Your current balance is $53.44.

data = ("John", "Doe", 53.44)

format_string = "Hello"

print(format_string ... % data)

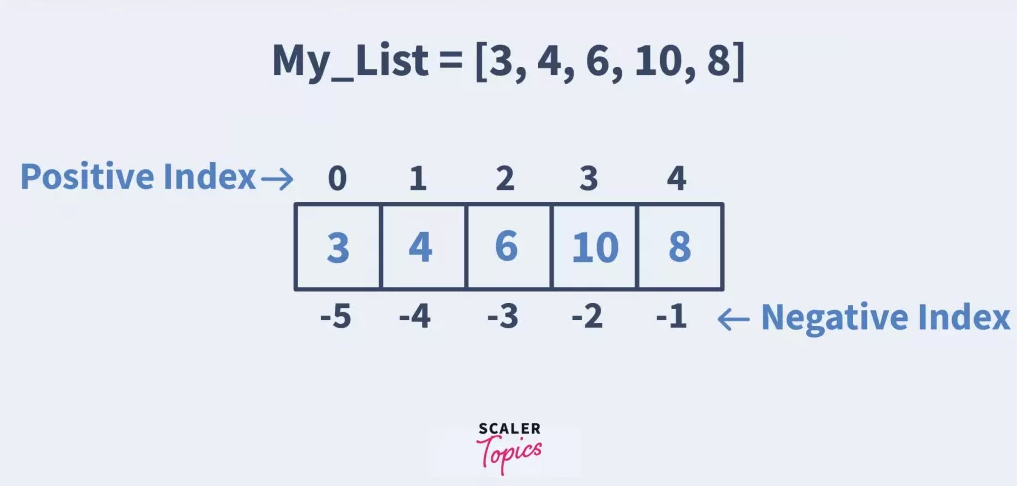

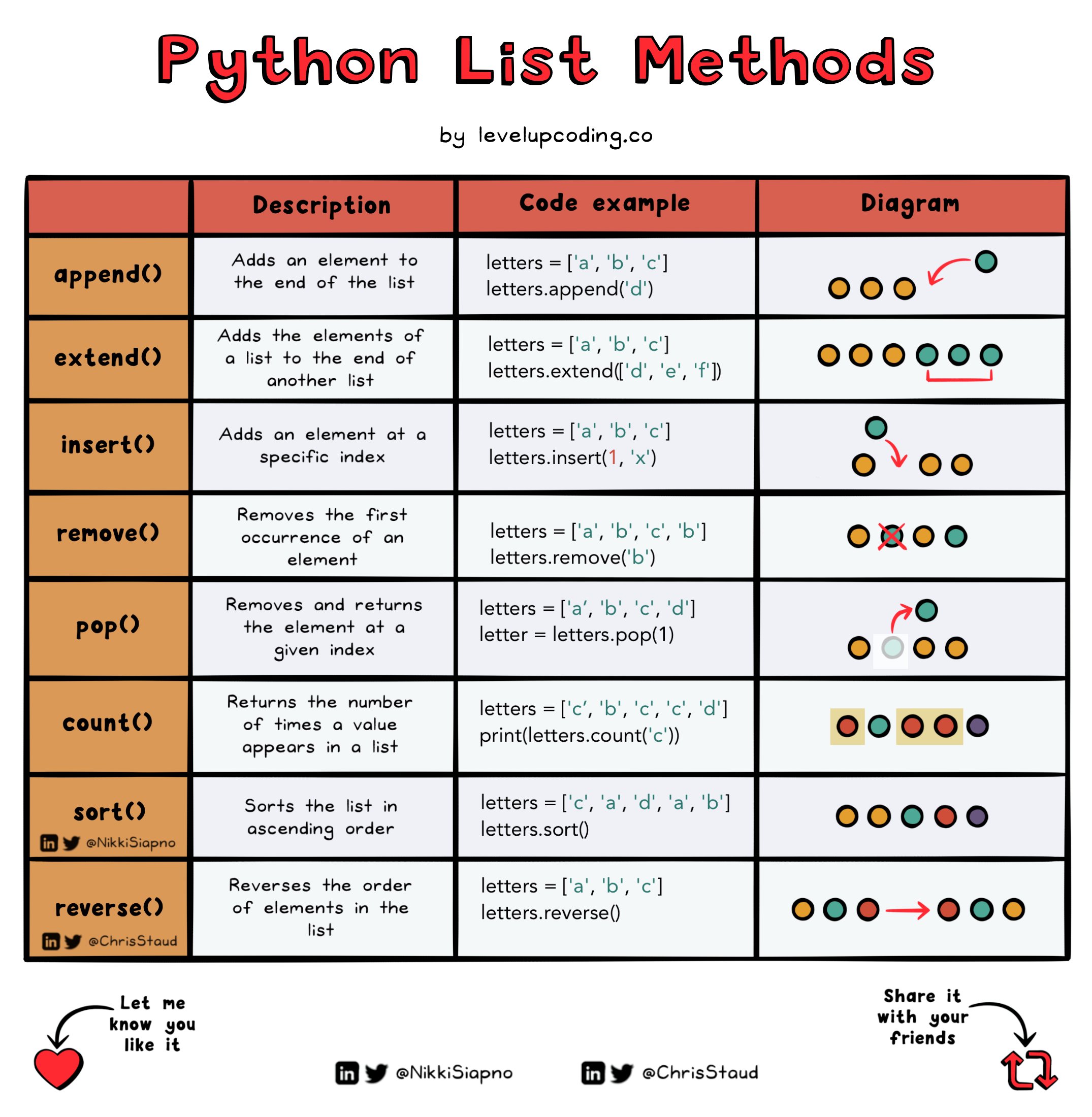

>Lists and Tuples

Lists

Lists are very similar to arrays. They can contain any type of variable, and they can contain as many variables as you wish. Lists can also be iterated over in a very simple manner.

try:

My_List = [3, 4, 6, 10]

print(My_List[0])

print(My_List[1])

print(My_List[2])

My_List.append(8)

print(My_List)

# prints out 8, 4, 6, 10, 8

for x in My_List:

print(x)

mylist = [1,2,3]

print(mylist[10])

# IndexError: list index out of range

Exercise

In this exercise, you will need to add numbers and strings to the correct lists using the “append” list method. You must add the number 9 to the “numbers” list, and the word ‘Architects’ to the “strings” list.

The result must be “I love Architects49 more than you”

numbers = [1,2,3]

strings = ['Shma', 'you', 'Design103']

# Hint

numbers.append(...)

strings.append(...)

print("I love " + strings[...] + str(numbers[...]) + str(numbers[...]) + " more than" + strings[...])

Tuples

Tuples are used to store multiple items in a single variable.

Tuple items are ordered, unchangeable, and allow duplicate values. A tuple is a collection which is ordered and unchangeable.

mytuple = ("apple", "banana", "cherry")

print(mytuple)

print(mytuple[0])

print(mytuple[1])

print(mytuple[2])

Tuple items are indexed, the first item has index [0], the second item has index [1] etc.

mytuple = ("apple", "banana", "cherry")

print(mytuple[1])

mytuple[1] = "coconut"

print(mytuple[1])

- Orders - When we say that tuples are ordered, it means that the items have a defined order, and that order will not change.

- Unchangeable - Tuples are unchangeable, meaning that we cannot change, add or remove items after the tuple has been created.

- Allow Duplicates - Since tuples are indexed, they can have items with the same value (like Lists)

Create Tuple With One Item

To create a tuple with only one item, you have to add a comma after the item, otherwise Python will not recognize it as a tuple.

thistuple = ("apple",)

print(type(thistuple))

#NOT a tuple

thistuple = ("apple")

print(type(thistuple))

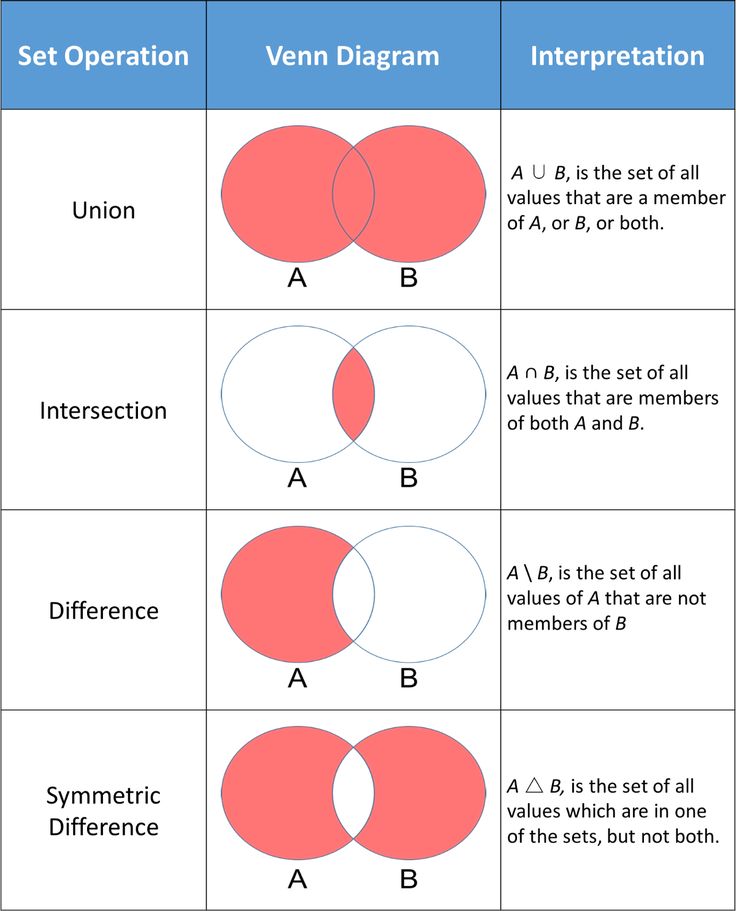

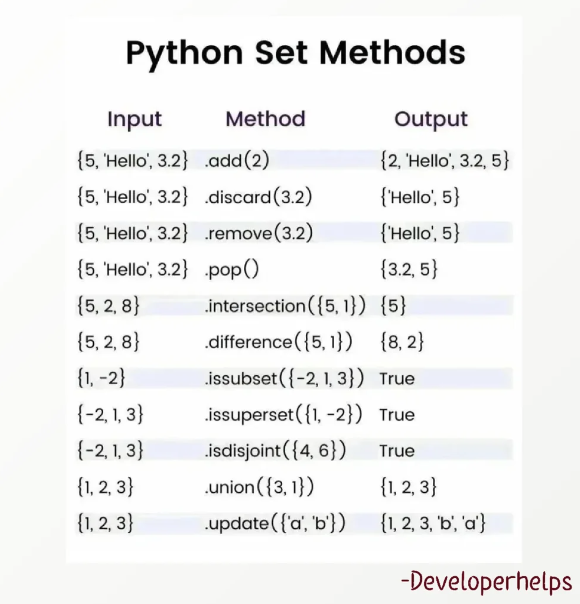

>Sets

A set is a collection which is unordered, unchangeable, and unindexed.

thisset = {"apple", "banana", "cherry"}

print(thisset)

- Note: Set items are unchangeable, but you can remove items and add new items.

Union

The union() method returns a new set with all items from both sets.

set1 = {"a", "b", "c"}

set2 = {1, 2, 3}

set3 = set1.union(set2)

# set3 = set1 | set2

print(set3)

Intersection

Keep ONLY the duplicates

The intersection() method will return a new set, that only contains the items that are present in both sets.

set1 = {"apple", "banana", "cherry"}

set2 = {"google", "microsoft", "apple"}

set3 = set1.intersection(set2)

# set3 = set1 & set2

print(set3)

Difference

The difference() method will return a new set that will contain only the items from the first set that are not present in the other set.

set1 = {"apple", "banana", "cherry"}

set2 = {"google", "microsoft", "apple"}

set3 = set1.difference(set2)

# set3 = set1 - set2

print(set3)

Symmetric Differences

The symmetric_difference() method will keep only the elements that are NOT present in both sets.

set1 = {"apple", "banana", "cherry"}

set2 = {"google", "microsoft", "apple"}

set3 = set1.symmetric_difference(set2)

# set3 = set1 ^ set2

print(set3)

>Conditions

Python uses boolean logic to evaluate conditions. The boolean values True and False are returned when an expression is compared or evaluated.

x = 2

print(x == 2)

print(x == 3)

print(x < 3)

The variable assignment is done using a single equals operator ”=”, whereas comparison between two variables is done using the double equals operator ”==”. The “not equals” operator is marked as ”!=”.

Boolean operators

The “and” and “or” boolean operators allow building complex boolean expressions.

name = "Nonny"

age = 18

if name == "Nonny" and age == 18:

print("Your name is Nonny, and you are also 18 years old.")

if name == "Nonny" or name == "Lawrence":

print("Your name is either Nonny or Lawrence.")

name = "Nonny"

age = 14

if name == "Nonny" and age != 18:

print("Your name is Nonny, but you are not yet 18 years old.")

print("Nonny" == "Nonny")

print(18 != 18)

The “in” operator

The “in” operator could be used to check if a specified object exists within an iterable object container.

name = "Nonny"

if name in ["Nonny", "Lawrence"]:

print("Your name is either Nonny or Lawrence.")

Python uses indentation to define code blocks, instead of brackets. The standard Python indentation is 4 spaces, although tabs and any other space size will work, as long as it is consistent.

statement = False

another_statement = True

if statement is True:

# do something

pass

elif another_statement is True: # else if

# do something else

pass

else:

# do another thing

pass

x = 2

if x == 2:

print("x equals two!")

else:

print("x does not equal to two.")

The ‘is’ operator

Unlike the double equals operator ”==”, the “is” operator does not match the values of the variables, but the instances themselves.

x = [1,2,3]

y = [1,2,3]

print(x == y) # Prints out True

print(x is y) # Prints out False

print(x is x) # Prints out True

The “not” operator

Using “not” before a boolean expression inverts it.

print(not False) # Prints out True

print((not False) == (False)) # Prints out False

>Loops

There are two types of loops in Python, for and while.

The “for” loop

For loops iterate over a given sequence.

primes = [2, 3, 5, 7]

for prime in primes:

print(prime)

For loops can iterate over a sequence of numbers using the “range” function.

# Prints out the numbers 0,1,2,3,4

for x in range(5):

print(x)

# Prints out 3,4,5

for x in range(3, 6):

print(x)

# Prints out 3,5,7

for x in range(3, 8, 2):

print(x)

“while” loops

While loops repeat as long as a certain boolean condition is met.

# Prints out 0,1,2,3,4

count = 0

while count < 5:

print(count)

count += 1 # This is the same as count = count + 1

“break” and “continue” statements

break is used to exit a for loop or a while loop, whereas continue is used to skip the current block, and return to the “for” or “while” statement.

# Prints out 0,1,2,3,4

count = 0

while True:

print(count)

count += 1

if count >= 5:

break

# Prints out only odd numbers - 1,3,5,7,9

for x in range(10):

# Check if x is even

if x % 2 == 0:

continue

print(x)

Can we use “else” clause for loops?

We can use else for loops. When the loop condition of “for” or “while” statement fails then code part in “else” is executed. If a break statement is executed inside the for loop then the “else” part is skipped. Note that the “else” part is executed even if there is a continue statement.

# Prints out 0,1,2,3,4 and then it prints "count value reached 5"

count=0

while(count<5):

print(count)

count +=1

else:

print("count value reached %d" %(count))

# Prints out 1,2,3,4

for i in range(1, 10):

if(i%5==0):

break

print(i)

else:

print("this is not printed because for loop is terminated because of break but not due to fail in condition")

Exercise

Loop through and print out all even numbers from the numbers list in the same order they are received. Don’t print any numbers that come after 237 in the sequence.

numbers = [

951, 402, 984, 651, 360, 69, 408, 319, 601, 485, 980, 507, 725, 547, 544,

615, 83, 165, 141, 501, 263, 617, 865, 575, 219, 390, 984, 592, 236, 105, 942, 941,

386, 462, 47, 418, 907, 344, 236, 375, 823, 566, 597, 978, 328, 615, 953, 345,

399, 162, 758, 219, 918, 237, 412, 566, 826, 248, 866, 950, 626, 949, 687, 217,

815, 67, 104, 58, 512, 24, 892, 894, 767, 553, 81, 379, 843, 831, 445, 742, 717,

958, 609, 842, 451, 688, 753, 854, 685, 93, 857, 440, 380, 126, 721, 328, 753, 470,

743, 527

]

# your code goes here

for number in numbers:

...

...

>Functions

What are Functions?

Functions are a convenient way to divide your code into useful blocks, allowing us to order our code, make it more readable, reuse it and save some time. Also functions are a key way to define interfaces so programmers can share their code.

block_head:

1st block line

2nd block line

...

Where a block line is more Python code (even another block), and the block head is of the following format: block_keyword block_name(argument1,argument2, …) Block keywords you already know are “if”, “for”, and “while”.

Functions in python are defined using the block keyword “def”, followed with the function’s name as the block’s name.

def my_function():

print("Hello From My Function!")

Functions may also receive arguments (variables passed from the caller to the function).

def my_function_with_args(username, greeting):

print("Hello, %s , From My Function!, I wish you %s"%(username, greeting))

Functions may return a value to the caller, using the keyword- ‘return’.

def sum_two_numbers(a, b):

return a + b

How do you call functions in Python?

Simply write the function’s name followed by (), placing any required arguments within the brackets.

def my_function():

print("Hello From My Function!")

my_function()

def my_function_with_args(username, greeting):

print("Hello, %s, From My Function!, I wish you %s"%(username, greeting))

my_function_with_args("John Doe", "a great year!")

def sum_two_numbers(a, b):

return a + b

x = sum_two_numbers(1,2)

print(x)

Exercise

xxx

...

...

...

>Dictionaries

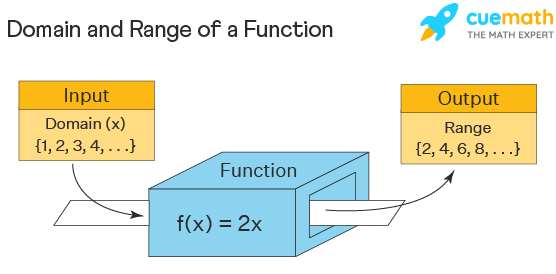

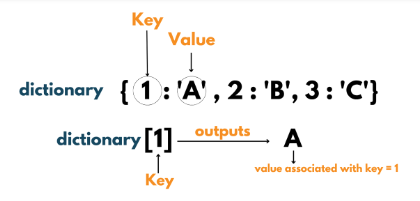

A dictionary is a data type similar to arrays, but works with keys and values instead of indexes. Each value stored in a dictionary can be accessed using a key, which is any type of object (a string, a number, a list, etc.) instead of using its index to address it.

phonebook = {}

phonebook["Nonny"] = 938477566

phonebook["Lawrence"] = 938377264

print(phonebook)

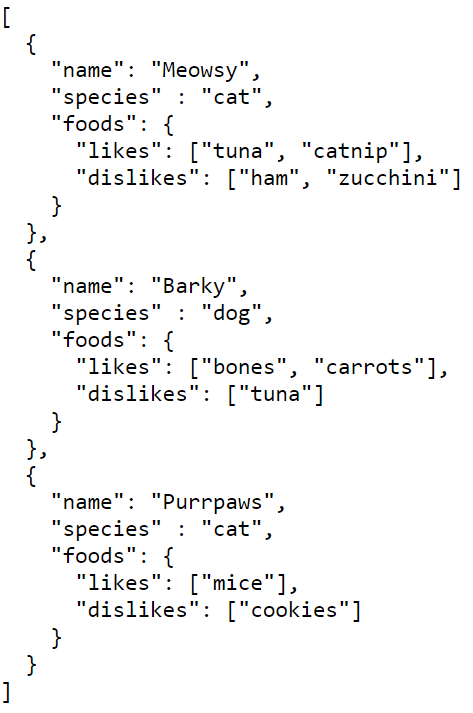

example to read json file to table ()

import pandas as pd

import requests

# URL of the JSON file

url = 'https://nontapatnon.github.io/python-course-master/other/animals-1.json'

# Fetching the JSON data from the URL

response = requests.get(url)

data = response.json()

# Normalize the JSON data into a flat table

df = pd.json_normalize(data)

# Convert lists in 'foods.likes' and 'foods.dislikes' to comma-separated strings

df['foods.likes'] = df['foods.likes'].apply(lambda x: ', '.join(x))

df['foods.dislikes'] = df['foods.dislikes'].apply(lambda x: ', '.join(x))

# Rename the columns for clarity

df = df.rename(columns={'foods.likes': 'foods_likes', 'foods.dislikes': 'foods_dislikes'})

# Now df is ready to use

print(df)

results:

| name | species | foods_likes | foods_dislikes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Meowsy | cat | tuna, catnip | ham, zucchini |

| 1 | Barky | dog | bones, carrots | tuna |

| 2 | Purrpaws | cat | mice | cookies |

Iterating over dictionaries

Dictionaries can be iterated over, just like a list. However, a dictionary, unlike a list, does not keep the order of the values stored in it. To iterate over key value pairs, use the following syntax:

.items()

phonebook = {'Nonny': 938477566, 'Lawrence': 938377264}

for name, number in phonebook.items():

print("Phone number of %s is %d" % (name, number))

.keys()

phonebook = {'Nonny': 938477566, 'Lawrence': 938377264}

for name in phonebook.keys():

print("Name is %s" % name)

.values()

phonebook = {'Nonny': 938477566, 'Lawrence': 938377264}

for number in phonebook.values():

print("Phone number is %d" % number)

Nested Dictionaries

A dictionary can contain dictionaries, this is called nested dictionaries.

child1 = {

"name" : "Emil",

"year" : 2004

}

child2 = {

"name" : "Tobias",

"year" : 2007

}

child3 = {

"name" : "Linus",

"year" : 2011

}

myfamily = {

"child1" : child1,

"child2" : child2,

"child3" : child3

}

print(myfamily["child2"]["name"])

# for x, obj in myfamily.items():

# print(x)

# for y in obj:

# print(y + ':', obj[y])